On August 24th, 1608, the British East India Company arrived on the coast of Western India with one purpose in mind: trade. India, up to this point, was the mecca of one of the world’s most prosperous trading routes, the Indian Ocean Exchange, offering goods such as cotton textiles, silk, sugar, and spices like pepper, cardamom, and ginger. Britain had never had access to these goods, and seeing their European counterparts, like the Portuguese and Dutch, monopolize those commodities fueled competitive imperial ambitions. So, with the Mughal Empire’s permission, they established the trading posts of Calcutta, Madras, and Bombay, acquiring the luxuries they had once never possessed. Although these trading ports primarily served British desires, they also laid the groundwork for interactions that would influence medical change in India in the centuries to come.

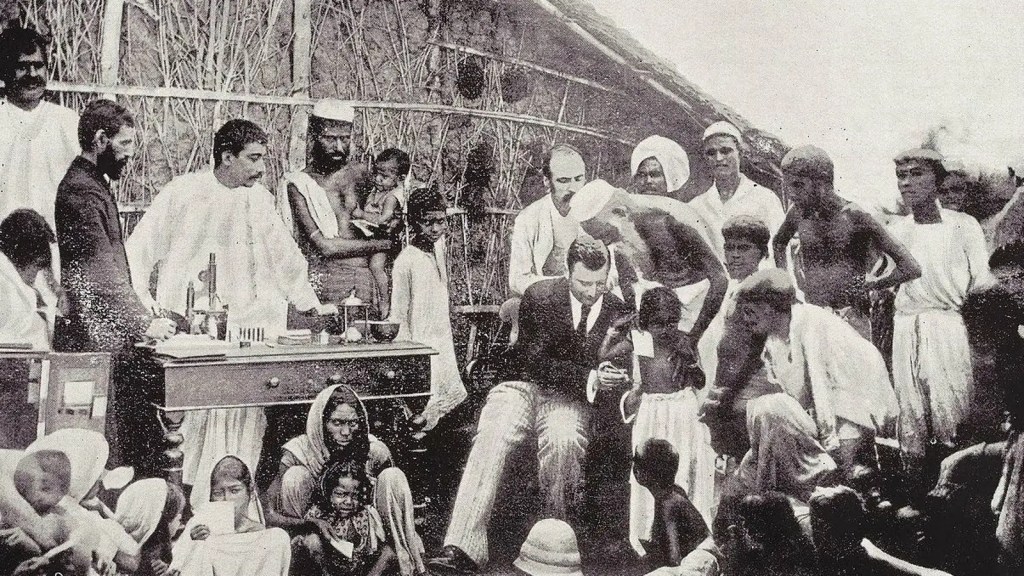

In 1760, Great Britain underwent a significant technological change: the Industrial Revolution. New methods of manufacturing appeared. Products that once took months to craft came out of factories in minutes. Entrepreneurs and industrialists gained an unprecedented amount of wealth. Yet, along with this growth came the second wave of British imperialism. Industrialization required raw materials to continue production for a mass market, but Britain did not have access to a constant source of such materials, which led them to look to other regions to supply their demands. One country – India – was the world leader in cotton production. The British already had trading relations with them, and so they began the slow process of colonization. Through a series of battles, alignment with local landowners, and frequent intervention in local conflicts, the British East India Company assumed total political control over India. As colonization deepened, the British established new medical institutions to support governance and authority over the conquered. However, in 1857, a mutiny of Hindu and Muslim troops pushed Great Britain to establish direct rule from the Crown, creating the British Raj. Thus began the era of British India, spurring transformations in medicine and public health for centuries to come.

The purpose of this essay is to explore how British imperialism affected medical policy in India. It will delve into the political, economic, and environmental factors that led to changes in medicine in British India, and why health policy changes were constructed to maintain colonial rule. The hope of this essay is to understand a certain aspect of British imperial dominance and connect it to broader trends in European colonization in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Although the British Raj lasted from 1857 to 1947, its rule of India was quite disorganized. Unlike its other colonies, British rule in India lacked a driving purpose. There was no “civilizing mission,” an ideology used by imperialists to justify colonial rule; instead, control was established to showcase the status of the British Crown and provide career opportunities to ambitious generals.1 Additionally, administration was diverse. At the top level ruled the British, but lower-level administrators were supplied by Indians through the Indian Civil Service (ICS). Now, how did these political factors affect public health? Before taking over official rule of India, Western medicine was spread through local interactions. When the East India Company arrived in 1600, ship surgeons came with them. Over time, medical departments in Bengal, Madras, and Bombay were established, often containing both military and civil medical services, laying the groundwork for a structured healthcare system. Colleges were also created, such as King Edward Medical College in Lahore in 1860, offering new paths for Western education and social mobility. Finally, by 1896, the British Raj established the Indian Medical Services (IMS) to unify medical departments across all Indian regions.2 Here, one must note how a long political process affected health policy in India. Although British motives were originally to establish commercial relationships and gain access to new goods, their actions of forming local hospitals and universities represent their desires for colonization, because there were no longer intentions to trade, but rather to spread influence. This is significant because by introducing their own medicine, they changed medical policy in India, which began to favor Western medical practices over traditional medicine. One example of this was at Calcutta Medical College, where Charles Archer, a British medical professor, gave an introductory lecture to his students on June 15th, 1859:

You will find those who profess to cure every disease by a vegetable dose… then brandy and salt… and pills to cure every ailment… This must not disconcert you… your profession will prevail, and these quixotic ideas will give way to the sober influence of truth.3

The practices Archer refers to are most likely local medical practices, such as Ayurveda and Unani. By juxtaposing the word “quixotic” with “truth,” Archer reveals a broader British intention to supplant traditional medicine in favor of Western ideals, as he casts a negative shadow on Indian beliefs. These practices would no longer be considered “correct” in British views, so they changed medical policy to favor their own customs. This replacement reflects a broader trend of policy change throughout British colonies, as education and Western values replaced traditional beliefs in governance. This idea of shifts in policy was further demonstrated through the British acts of medical centralization in India, as colonial authorities introduced standardized regulations for medical practice. Specific licensing and curricula were established, and oftentimes, these requirements marginalized traditional practitioners.4 This practice of consolidation was common throughout all sectors of the British Raj, as direct chains of command were needed to establish control of the region. Therefore, the British political practices of gradual colonization and centralization effectively shifted medical practices and policies in India away from traditional and cultural practices in favor of Western medical practices, forever reshaping the image of public health in India.

The original aim of Indian colonization was to supply raw goods for the economic transformation of the Industrial Revolution. Yet how and why did this change colonial India’s medical policy? One example can be found in the development of railways. To funnel different crops and goods produced in internal regions to the coast, new modes of transportation were developed. The most efficient was arguably the railroad, and when developed alongside irrigation systems in colonial India, mosquitoes invaded the drainage pipes, spreading malaria. Railroads were no longer just tools of economic growth, but also became transmitters of disease. In order to protect their economic interests, British officials intervened to establish new health institutions and conducted research to better understand and control malaria.5 This instance illuminates how medical policy changed in India due to economic factors. The fact that the British government only stepped in to transform local infrastructure when it harmed their financial interests shows that the change in medical policy in colonial India was not meant to serve the needs of the Indian people, but rather to feed the economic needs of the Crown and industrialists back in Britain. What further illustrates this argument is that, oftentimes, the introduction of Western medicine in India was driven largely by the requirements of the colonial administration. Medical departments served primarily British military personnel and colonial officials, rather than the indigenous population, in order to maintain administrative efficiency and control.6 However, the need for efficiency was caused by economic constraints. Limited financial resources often pushed the British Raj to focus on cost-effective measures like preventive care, like vaccinations and sanitation, over curative care.7 The result of this was shown in the 1946 Bhore Committee Report, which described the effects of an absence of curative care in colonial India:

If it were possible to evaluate the loss, which this country annually suffers through the avoidable waste of valuable human material and the lowering of human efficiency through malnutrition and preventable morbidity, we feel that the result would be so startling that the whole country would be aroused and would not rest until a radical change had been brought about.8

The waste the report refers to reinforces the point that British-Indian medical policies were built to be so cost-efficient that they did not take into account people in need of greater treatment. The fact that the text acknowledges these deaths as preventable reveals that the main British intention was to extract wealth from India with the lowest possible expenses. Thus, medical policies in colonial India were not constructed to help the local people; rather, they prioritized the well-being of the British and sought to eliminate the disease-stricken whose care required greater financial resources, illustrating the brutality imperialism inflicted on colonized peoples.

What was common in the British colonization of India was the adaptation of medical policy to support imperialist ambitions. The changes discussed occurred due to political and economic reasons. Yet how, when deploying troops to conquer new Indian regions, did the British adapt medical policy to the new environment? Medical topography was the answer. To prevent troops’ exposure to new diseases, medical officers developed written reports identifying areas with favorable conditions for placing barracks and cantonments, allowing British officials to minimize mortality rates and enhance military efficiency.9 This again shows how the British shifted medical policy to support imperialist ambitions, as their main aim was to be as safe as possible when conquering local peoples, rather than helping to end poor conditions themselves. Thus, in colonial India, British medical policy was focused on adapting to local environmental conditions rather than mitigating diseases and unsanitary conditions. However, it is interesting to note a counterargument to this idea. Oftentimes, medical officers would use medical topography reports to advocate for better sanitation and health standards in Indian cities. One example of this was Sir James Ranald Martin, who pushed for sanitary reforms and public health measures in Calcutta, where overcrowding and inadequate infrastructure exacerbated health issues. He detailed his findings in Notes on the Medical Topography of Calcutta, which he even used to argue for the standardization of medical reports across all districts to prevent outbreaks.10 However, although it may seem that colonial medical policy benefited the local Indian people, one must consider the motives behind environmental and medical policy changes. Many medical officials sought to achieve colonial stability in order to carry out British rule. An outbreak could have caused rifts within the population, potentially challenging the authority of the government and disrupting the labor supply that supported British industrial needs. Therefore, although medical policy in colonial India did help improve health and sanitation standards for the local people, the motives behind these changes were to subdue the population and maintain administrative efficiency in the face of a complex environment.

All in all, changes in medical policy in colonial India occurred to support British imperial rule. Politically, the consolidation of power led to a shift away from traditional medicine toward standardized Western medical practices. Economically, medical policies were used to maximize resources and minimize costs, prioritizing British lives over those of ill local people. Environmentally, health policies allowed for easier governance over a vast population. Now, take a look at these conclusions. All of them share one similarity – that imperialism caused policies to favor those in power. Whether it be the British, Dutch, French, or others, when the world was under European rule, change occurred at every level. Most of the time, this change served to satisfy imperial ambitions. So, when thinking about the history of imperial policy, one must consider its context. Who constructed the policy? Why was it put in place? What was it influenced by? These questions will help all of us understand what led to the current global scale of power – and maybe, just maybe, we can use these lessons to help navigate the complex reality we face today.

Notes

- Jon Wilson, The Chaos of Empire: The British Raj and the Conquest of India (New York: PublicAffairs, 2016), https://apnaorg.com/books/english/the-chaos-of-empire-the-british/the-chaos-of-empire-the-british.pdf.

- Muhammad Umair Mushtaq, “Public Health in British India: A Brief Account of the History of Medical Services and Disease Prevention in Colonial India,” Indian Journal of Community Medicine 34, no. 1 (2009): 6–14, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2763662/.

- Charles Archer, An Introductory Lecture Addressed to the Students of the Calcutta Medical College, on the 15th June 1859 (Calcutta: [Publisher unknown], 1859), https://archive.org/stream/dli.ministry.03246/22166.132%2520D%2520103%25282%2529_djvu.txt.

- Ziyue Bi, “Colonialism and the Transformation of Traditional Medicine,” Research Archive of Rising Scholars (2024), https://research-archive.org/index.php/rars/preprint/view/1938.

- Mushtaq, “Public Health in British India,” 6–14.

- Veena Sriram, Vikash R. Keshri, and Kiran Kumbhar, “The Impact of Colonial-Era Policies on Health Workforce Regulation in India: Lessons for Contemporary Reform,” Human Resources for Health 19, no. 100 (2021), https://human-resources-health.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12960-021-00640-.

- Mushtaq, “Public Health in British India,” 6–14.

- Deepak Kaul, “Indian Medical Research: Perception and Paradox,” Annals of Neurosciences 21, no. 4 (2014): 128, https://annalsofneurosciences.org/journal/index.php/annal/article/viewArticle/632.

- Wendy Jepson, “Of Soil, Situation, and Salubrity: Medical Topography and Medical Officers in Early Nineteenth-Century British India,” Historical Geography 32 (2004): 137–155, https://dhjhkxawhe8q4.cloudfront.net/nebraska-journals-wp/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/16190107/08HG32-Jepson.pdf.

- James Ranald Martin, Notes on the Medical Topography of Calcutta (Calcutta: G.H. Huttmann, 1837), https://archive.org/details/b22274777.

Bibliography

Archer, Charles. An Introductory Lecture Addressed to the Students of the Calcutta Medical College, on the 15th June 1859. Calcutta: [Publisher unknown], 1859. https://archive.org/stream/dli.ministry.03246/22166.132%2520D%2520103%25282%2529_djvu.txt.

Bi, Ziyue. “Colonialism and the Transformation of Traditional Medicine.” Research Archive of Rising Scholars (2024). https://research-archive.org/index.php/rars/preprint/view/1938.

Jepson, Wendy. “Of Soil, Situation, and Salubrity: Medical Topography and Medical Officers in Early Nineteenth-Century British India.” Historical Geography 32 (2004): 137–155. https://dhjhkxawhe8q4.cloudfront.net/nebraska-journals-wp/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/16190107/08HG32-Jepson.pdf.

Kaul, Deepak. “Indian Medical Research: Perception and Paradox.” Annals of Neurosciences 21, no. 4 (2014): 128. https://annalsofneurosciences.org/journal/index.php/annal/article/viewArticle/632.

Martin, James Ranald. Notes on the Medical Topography of Calcutta. Calcutta: G.H. Huttmann, 1837. https://archive.org/details/b22274777.

Mushtaq, Muhammad Umair. “Public Health in British India: A Brief Account of the History of Medical Services and Disease Prevention in Colonial India.” Indian Journal of Community Medicine 34, no. 1 (2009): 6–14. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2763662/.

Sriram, Veena, Vikash R. Keshri, and Kiran Kumbhar. “The Impact of Colonial-Era Policies on Health Workforce Regulation in India: Lessons for Contemporary Reform.” Human Resources for Health 19, no. 100 (2021). https://human-resources-health.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12960-021-00640-.

Wilson, Jon. The Chaos of Empire: The British Raj and the Conquest of India. New York: PublicAffairs, 2016. https://apnaorg.com/books/english/the-chaos-of-empire-the-british/the-chaos-of-empire-the-british.pdf.

Leave a comment